We Built the Web with Tables and Luck

I learned to build websites on a Windows machine that had Homesite, Notepad.exe, and not much else. No version control. No devtools. No frameworks. The screen was 800 pixels wide (1024 is you were blessed) and that was that. People cared about megahertz. Every layout had to fit inside it, or risk breaking.

But all my troubles, and my career, started earlier than that.

Before the web was graphical, I found it in text. My secondary school in Ireland, rare for the time (nearing the end of the last millennium), had a single dial-up internet connection. I think it was 28.8kbps, running on a VAX/VMS system. This was the lone computer in our Computer Room that had the internet.

All the other computers were Apple IIGSs, which had replaced Apple IIe, which had many years prior replaced the brown Commodore 64s (one of which I had bought in the sell-off and served as my very first computer and where I learned to code). Please remember that the “64” in Commodore 64 didn’t mean the 64th version – it meant 64 KB in memory. An outlandish number in 1982.

This lab, these computers, this was the life’s work of Mr. Michael Moynihan, a math teacher who wore a white lab coat in class, and to whom I’m forever grateful. But I’m going off topic.

I didn’t care about the system details, it wasn’t really a choice. In an all-boys Catholic school a brave soul could download an 80 KB JPEG of Pamela Anderson if you were willing to wait 30 minutes and maybe restart the download once or twice. Or spoof emails from open SMTP servers. I just wanted to download guitar tab text files from FTP servers hosted on university servers in the US. That was my motivation: not to play these on a guitar, but to connect to something far away, and to hoard information. Maybe I’d learn how to play “Wish You Were Here” along the way, but that was just a bonus (I never did).

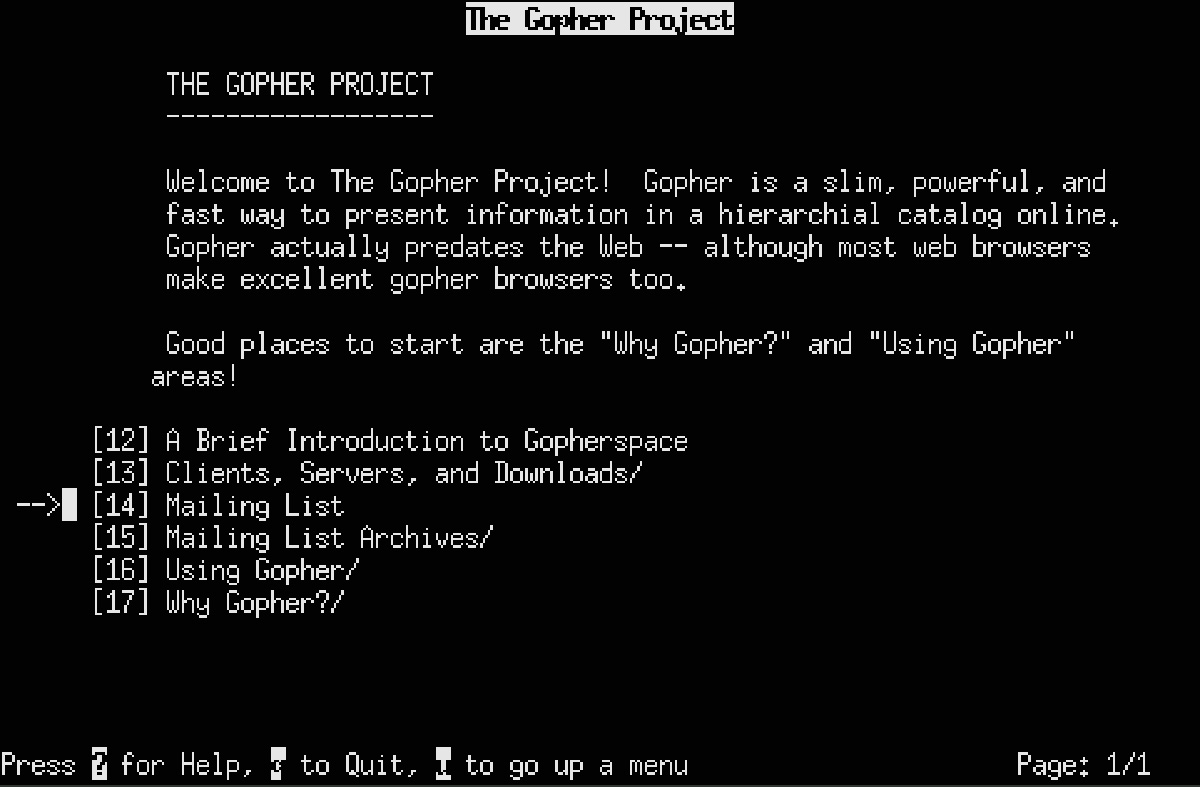

I’d tailgate into the computer rooms at the nearby university, UCC, and sit at terminals navigating the world with Lynx and Gopher. It was all text, organized in hierarchies that somehow felt both chaotic and full of possibility. Then came “hyperlinks.”

Hyperlinks changed everything. The idea that one piece of text could lead to another, across the room or across the world, was a revelation. That was the moment I knew I wanted to be part of whatever this future was.

I was already hooked by the idea of navigating through linked documents, but the moment I discovered “View Source” that was it. That was the gateway. Every site became a tutorial. You could inspect, borrow, remix. No gatekeepers, no IDEs, just a text editor and curiosity. If Gopher taught me that the internet was interconnected, View Source taught me that it was structured, and writable, by anyone willing to try.

I paid my dues slicing designs into tiny GIFs in Photoshop (or maybe Paint Shop Pro), carefully exporting each sliver so I could reconstruct them with HTML tables. Spacer GIFs were how you made spacing work. GIFs were also for static images not just for animation. Rounded corners meant four images. Background gradients came from JPEGs.

I figured out how to get one frame to talk to another. Not an iframe, just plain <frameset>. It felt like magic. Then came the days where that magic turned into a mess of scrollbars, nested windows, and analytics that couldn’t track anything properly.

Dreamweaver, from Macromedia, gave us one of the first usable HTML WYSIWYG editors, and then betrayed us with terrible generated code.

I wrote scripts in JavaScript, and sometimes in VBScript, because you had to. Netscape and IE were at war, and they spoke different dialects. For a while, it looked like we might need to write everything twice.

You have to understand the mental shifts we went through. We started with static HTML files – what you uploaded was exactly what users saw. But even that was challenging because browsers rendered the same markup completely differently.

With scripting languages you could change the page after it loaded using JavaScript (or VBScript or JScript). Suddenly the page could respond to clicks, validate forms, show/hide content. That felt revolutionary. It really was though.

Add in server-side scripts in the cgi-bin directory (usually) – now you could use Perl or PHP to generate completely different HTML based on who was visiting or what they requested. The age of guestbooks and counters began.

These felt like three separate and competing worlds at first. Now we layer them together without thinking.

And just as we were getting familiar with that, someone remembered you could send silent requests back to the server using HTTP 204 responses to get even more server-side content in the form of HTML fragments.

We did all this before anyone called it “AJAX,” before Gmail popularized the concept. Truly we were living in the future. Except, of course, you had to write two versions of xmlHttpRequest: one for IE, one for everything else.

Firebug browser extension changed everything too. Suddenly I could see the DOM. I could live-edit CSS. I could inspect things in a way that made sense. Before that, you debugged with alert(), luck, and the patience of a burning saint.

Time passes. We monitored browser stats. Every drop in Internet Explorer 6 usage felt like a milestone. It was a countdown to freedom. We’d check, hoping the numbers would dip below some self-imposed threshold so we could stop supporting it.

Every time we got close, someone on the business side would remind us: corporate users couldn’t upgrade. Legacy systems, locked-down environments, all chained to old versions. So we carried on supporting IE6, then IE7, and later even IE9, long after we’d mentally moved on.

It wasn’t just the front-end that changed. The entire foundation of the web was being rewritten underneath us. Instead of negotiating a multi-year contract for a physical data center, you could now spin up servers instantly with just a credit card and AWS. Tools, infrastructure, workflows. Everything was shifting.

And now we are here, “the future“. Apps, walled gardens, HTTPS, the cloud, and the responsive web. We don’t watch browser usage to track when we drop support but rather when we can drop shims and go all-in with newly released features. Our browsers force updates which is a much lesser sin than inertia. We still have px and % for managing length, but also em, rem, pt, pc, in, Q, mm, cm, vw, and calc came along (though I suspect many were always there).

Sometimes I think we’ve just been reinventing old ideas with better tools. We gave up tables for layout, then invented flexbox to do table-like layout. We used AJAX to grab HTML fragments. Then we abandoned that in early React era, only to come back and say we invented SSR or “hybrid rendering”, it’s faster to render it server-side and that is a new thing. We abandoned image maps. Early websites were semantic and structured with HTML first, styling and interactivity layered on. Then JS-heavy SPAs took over and look where we might be headed again.

We wrapped our hacks in cleaner syntax or integrated them at the browser level, but they’re still solving the same problems.

I don’t miss those days. But I’m glad I had them. They taught me how to make things work, not just the right way, but any way.

This is just one path through web development’s early stages, and a bit of idealized hindsight. If you were there, your memories might be different, and if you’re here now, building with today’s tools, maybe some of this just sounds like grumbling. That’s fair.

For those of us who learned by view source and wrestling with table layouts, there’s something both nostalgic and instructive about seeing how the fundamentals keep cycling back, usually with better tools.